03 July 2021

Digital restorations bring new life to classics of Czechoslovak cinema

Digital restorations bring new life to classics of Czechoslovak cinema

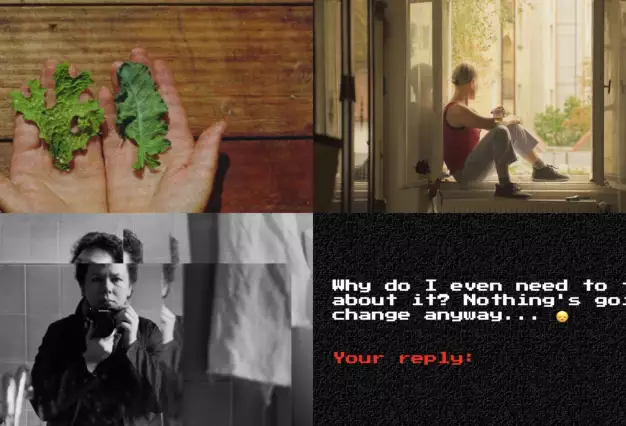

The first international recognition achieved by postwar Czechoslovak cinematography was the award garnered by The Strike (1947) at the Venice Film Festival. This social drama about the Kladno miners’ strike of 1889 represented the artistic peak of the brief period between the nationalization of the country’s film industry in 1945 and the Communist Party coup three years later.

Article by Martin Šrajer for CZECH FILM magazine / Summer 2021

After World War II, the quality and number of films made in Czechoslovakia declined. However, the adaptation of literary works, accounting for up to a third of postwar production, continued to maintain a high standard. Karel Steklý, who first won attention thanks to his directing of The Strike, based on a book, was just one example of this.

After serving as director of the Liberated Theater in the 1930s, inventing gags for actors Jiří Voskovec and Jan Werich, Steklý established himself as a screenwriter at Barrandov Studios in Prague during World War II, working often with Martin Frič. It was under Frič’s artistic direction that Steklý shot the mining drama The Breach in 1946, carrying on the socialist tradition in Czechoslovak film established by Such Is Life (1929), Dawning (1933), and Battalion (1937). The Breach — the first film produced after nationalization of the country’s film industry — was based on a story by Jan Morávek set in the 1860s, and with its theme of conflict between wealthy townspeople and poor miners, it offered a hint at Steklý’s future creative direction.

Class conflict also stands at the center of the novel on which The Strike was based: Siréna (The Siren), published in 1935 by Marie Majerová, a Communist Party member. Much to her chagrin, however, Steklý incorporated just two chapters from her mosaic novel following four generations of the working-class Hudec family in Kladno. Not only that, but while Majerová emphasized dialogue, Steklý was more concerned with pictorial representation. He envisioned the film as less talkative and more like the “crack of a whip,” and ultimately it was his vision that won out.

The Strike, Steklý’s second look back at the history of the workers’ movement after The Breach, takes place in the late nineteenth century as Kladno miners are preparing to strike over low wages and unacceptable working conditions. The smelters join their cause, but the arrogant mine owner calls in the army to break the strike. The compelling story is underlined by the expressive camerawork of Jaroslav Tuzar, the somber music of E. F. Burian, and the editing of Jan Kohout, inspired by Soviet montage to evoke the industrial atmosphere. By combining a touching individual drama with social issues, Steklý succeeded in calling attention to the exploitative practices of the unscrupulous managerial class.

Although shot in the spirit of socialist realism, with a relatively straightforward moral dividing line, The Strike is characterized by its sober mood, its authentic depiction of the environment, and its matter-of-fact approach to the characters. Unlike later socialist dramas, the workers here are not poster children, at times acting with an instinctive animalism. The acting was highly praised, especially the deeply emotional performance by Marie Vášová in the role of Hudcová, the mother of Hudec the smelter.

The Strike premiered in Czechoslovak cinemas in April 1947. Less than six months later, the rest of the world got the chance to discover it, thanks to its appearance at the eighth annual Venice Film Festival. But originally Čapek’s Tales (1947), directed by Frič, was the sole picture from Czechoslovakia nominated for the main competition. It was only at the last minute, thanks to the urging of A. M. Brousil, a member of the Czechoslovak delegation to the festival, that a copy of Steklý’s film was hastily sent to Italy. The Strike, captivating jury and audience alike with its universal subject matter and mature cinematic language, won the Golden Lion. In addition to the main prize, it also received the International Film Music Award.

Winning this pair of awards at such a prestigious festival turned The Strike into a propaganda tool used to demonstrate the maturity of the country’s nationalized film industry. A political bent is also visible in Steklý’s subsequent work, which in addition to his two films based on Jaroslav Hašek’s classic novel The Good Soldier Švejk, includes Darkness (1950; based on the 1913 novel Temno by Alois Jirásek), and Anna the Proletarian (1952; based on the 1928 novel Anna proletářka by Ivan Olbracht). However, in these films the intimate atmosphere and stylistic unity play second fiddle to Communist ideology.

Vojtěch Jasný also celebrated the building of socialism in his first films—documentaries he and Karel Kachyňa created in tandem as early graduates of the FAMU film school in Prague. During a trip with the Army Art Ensemble, for example, they shot several optimistic portraits of life in China. Jasný’s independent feature debut was the military-themed September Nights (1956). A year later, he wrote the first version of a modern fairy tale about justice and desire, titled The Cassandra Cat. However, the picture wasn’t made until 1963. In the meantime, Jasný shot Desire (1958), a quartet of stories based on the four seasons of life, and Pilgrimage to the Virgin Mary (1961), a comedy. Both works foreshadowed The Cassandra Cat: Desire with its lyrical humanism, and Pilgrimage with its humor and satire.

The Cassandra Cat takes place in a picturesque Czech town where one day a traveling magician shows up with his assistant Diana and a cat capable of revealing people’s hidden nature. Under the gaze of the magical animal, everyone turns a different color according to their true character: liars turn purple, lovers red, thieves gray, and the unfaithful yellow. When the cat is abducted by bigwigs in town, fearful of losing their positions, children from the local school set out to rescue him.

Jasný’s coauthors on the screenplay were Jiří Brdečka and Jan Werich, the latter of whom also plays a double role in the film. To this day, the parable of hypocritical morality appeals to audiences not only due to Werich’s joviality, but also because of the visual sensibilities of the director, who worked closely with his DOP, Jaroslav Kučera, on the film’s artistic concept. A number of innovative trick scenes, requiring, among other things, the use of special colored makeup, led to extended shooting times.

The Cassandra Cat, brimming with color and verbal wit, was first seen by visitors to the Cannes Film Festival in May 1963, where it shared the Special Prize together with Japanese director Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962). It also received an award from the Supreme Technical Commission. Then, in July, it was shown in Locarno, and in September 1963, Jasný’s féerie finally hit domestic cinemas. By the end of the year, it had been seen by 1,310,291 Czechoslovak moviegoers. The message and technical achievements of The Cassandra Cat were also highly praised by critics.

After 1968, however, the film found itself on a list of banned works. Jasný still managed to complete his long-in-coming historical fresco All My Good Countrymen. But this marked the end of his Czechoslovak career for years to come, as in 1970 he left the country and went into exile.

Now, cinema buffs can watch digitally restored versions of both The Strike and The Cassandra Cat the way they were seen by their original audiences. For Steklý’s The Strike, restored at UPP and Soundsquare studios, the original negative shot on black-and-white Agfa served as the primary source, with duplicates used for missing or damaged frames. The Jasný picture was restored at L’Immagine Ritrovata film restoration laboratory in Bologna, Italy, under the supervision of the Národní filmový archiv, Prague. The source image material for The Cassandra Cat was an intermediate of positives on Eastmancolor and an original negative on Eastmancolor and Agfa. Color and brightness settings were based on a reference copy lent by the Filmoteka Narodowa in Poland.

The author of this article thanks to Tereza Frodlová from the "Národní filmový archiv, Prague" for the information on digital restoration.