19 August 2019

The harrowing journey of a young boy through Europe’s darkest hours

The harrowing journey of a young boy through Europe’s darkest hours

With Václav Marhoul´s ambitious and long-awaited project The Painted Bird, Czech fiction film is returning to the Venice Film Festival competition after 25 years.

Interview with Václav Marhoul for Czech Film Magazine / Fall 2019

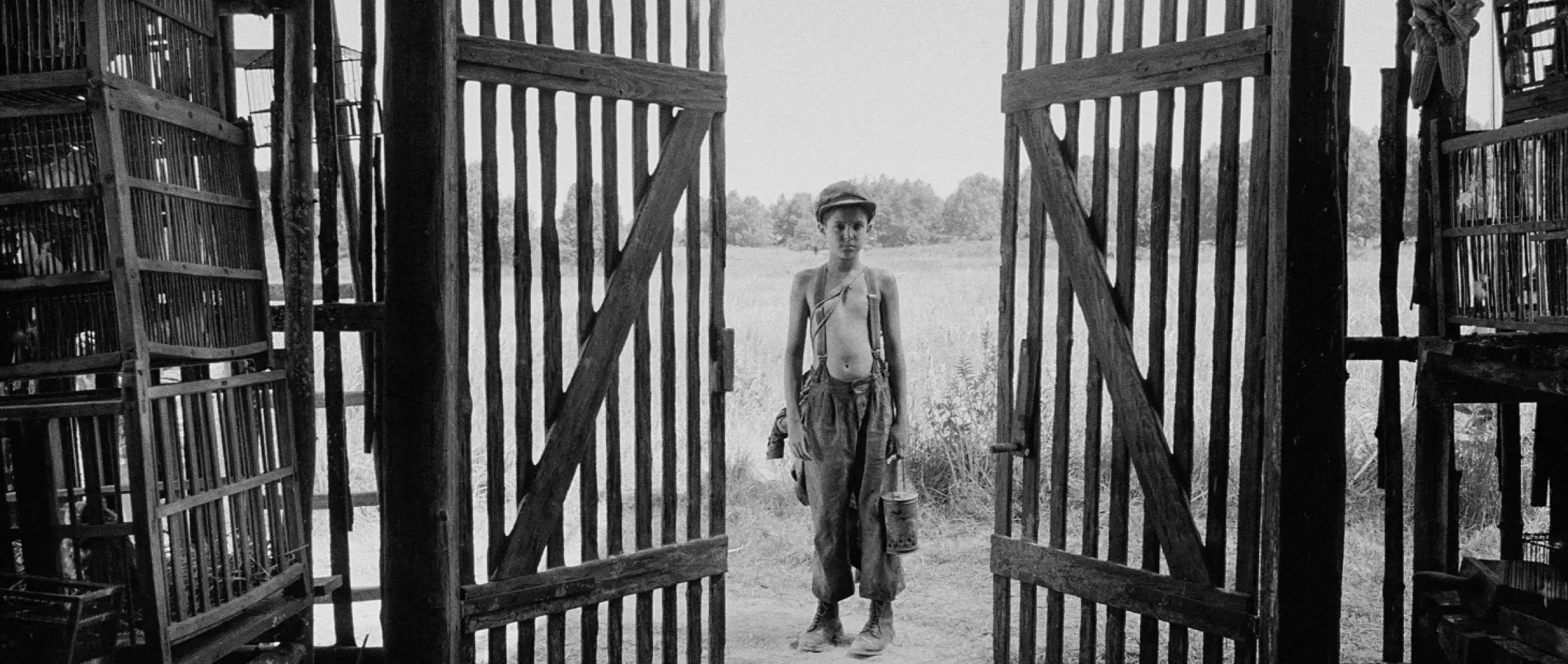

Based on the acclaimed Jerzy Kosiński novel, The Painted Bird tells the story of The Boy, entrusted by his persecuted parents to an elderly foster mother. The old woman soon dies and The Boy is on his own, wandering through the country-side, from village to farmhouse. As he struggles for survival, The Boy suffers through extraordinary brutality meted out by the ignorant, superstitious peasants and he witnesses the terrifying violence of the efficient, ruthless soldiers, both Russian and German.

When the war ends, The Boy has been changed, forever.

Why The Painted Bird? What does Jerzy Kosiński’s book mean to you?

Kosiński’s novel affected me very strongly and deeply. As a scriptwriter, director and indeed, equally as a producer, I make my decisions from the heart.

I never calculate, never speculate. Immediately after finishing the book, I said to myself: “I have to film this. I have to.” The Painted Bird is not a war film, nor even a Holocaust film. I believe that it is a completely timeless and universal story - of the struggle between darkness and light, good and evil, true faith and organized religion and many other opposites.

The story forced me to ask myself many unpleasant questions and to struggle, alone, for the answers. I was left in doubt about the purpose and fate of Homo sapiens as a species and these doubts hurt so much that I had to hang on to anything positive. And this is precisely where the magic lies: only in darkness could I see light. Through confronting evil, I arrived at the unshakeable conviction that good and love must necessarily exist.

The book was seen as autobiographical, but then, Kosiński was accused of having invented most of the situations, of writing a work of fiction and imagining horrifying situations that he himself never experienced.

Yes, I know. Kosiński during his lifetime made a mistake when he said that it was his personal autobiography. This was not true. But to understand why he did it, it is necessary to know his life, his spirit and his thoughts. For me, whether the book reflects his own experiences or not is completely irrelevant, because the essential element of a work of art is not its biographical truth, but its truthfulness.

Is the film different from the book? How long did you work on the screenplay?

A film, unlike a novel, is based not on words but on images and no adaption to film can match what been created in the imagination of the reader.

The camera is absolutely uncompromising: it offers the viewpoint of the director and no one else. An adaptation can only be successful if the aesthetic concept of the film, the narrative style and the message of the story re-create for the viewer the emotional and intellectual impact the book would have on its readers. I wrote seventeen versions of the screenplay, and this process took three years.

The book itself is full of cruel and disturbing scenes. How did you work with these often-brutal forms of violence?

I tried to be measured and objective throughout. I wanted audiences to be able to bear the scenes of brutality. My hope was that the black and white images, the framing, the pacing and the expansive setting of the countryside, would give the viewers the emotional room to seriously reflect on the acts of violence that the boy sees and endures. I avoided shocking, fast effects (that reduce responsibility) as well as any gratuitous lingering (that would implicate the viewer too much). I trust the viewers will never feel trapped or that any of the events portrayed are inevitable.

The Painted Bird is a meditation on evil, but also, the opposite: goodness, empathy, love. In their absence, we inevitably turn to those values. When we do have glimpses of good and love in The Painted Bird, we appreciate their essence and we yearn for more. This is the positive message of the movie—the human longing for good. When The Boy cries: ‘I want to go home!’, we too want to go home, to a safe place of love. Anything else seems absurd.

In The Painted Bird it becomes even more painful when such a cruel story affects a small child.

Adults have their own pasts, which they are aware of, and at the same time they can imagine a future. But this is not true for a child. The past is an unbelievably shallow body of water, where it’s not possible to swim. And the future cannot be imagined at all. A child, basically, can only think a few days ahead. What will happen in a month is unknowable. Several clinical psychologists have concluded that children, paradoxically, accept difficult reality far more easily than adults do. They take it as it is. And of course, this is the quality that helps children survive by allowing them to believe that the terrible things around them are normal. Something like this happens to our main character, The Boy, who is saved but perhaps irrevocably damaged by the very resilience that allowed him to tolerate horror. Still, I am convinced that there is always a way back.

You used black-and-white 35 mm film stock. Why?

I’m one of those filmmakers who – even despite today’s amazing possibilities of digital filming – is convinced that the negative is basically irreplaceable and that it gives film a kind of magic. The negative is more authentic, especially for something like “The Painted Bird”, which is in black and white precisely to reinforce the basic narrative line. Filming it in colour would have been a catastrophe. It would have looked entirely unconvincing, fake, commercial.

The main role of the child is performed by Petr Kotlár, whom you didn’t find through casting, but by a chance meeting. How did this happen?

It happened a few years before filming, in the beautiful medieval Czech town known as Český Krumlov. And there, one fine day, I saw him … And I felt, literally felt, just as I did with the book, that casting this child would be the right decision. He was The Boy. Such a risk … Petr Kotlár, a non-actor, a little boy without any experience in front of a camera.

How did you prepare Petr for such demanding film work?

I did only two things. First, we had camera tests. I had no idea whether he would even be able to go in front of the camera. Perhaps despite his clearly strong, extrovert nature and heart-felt desire to perform, he would just freeze. I called myself a fool, because I had to start shooting in a few months, and I had staked it all on him, intuitively. I didn’t have anyone else in reserve. Then, thank God, I was helped enormously by a very well-known Czech actress who worked with him the entire day. We tested the main emotions and her task was to help him create an atmosphere of fear, sorrow, laughter, tears… It worked out. Petr passed with flying colours. Secondly, I had him take psychological tests. And these too he passed without any trouble. For the entire period of shooting, for each of the 102 filming days in the course of almost two years, there was a chaperone with him who took care of him in between the scenes. There was not a second where he had to sit by himself and wonder what to do.

And I was able to guide him as a director through his beloved dog, Dodík. So when, for instance, I needed him to be sad, I’d suggest: “Petr, imagine that Dodík ran away somewhere and you can’t find him.”

Acting alongside Petr were many major international stars: Stellan Skarsgaard, Harvey Keitel, Udo Kier, Julian Sands, Barry Pepper... How did you get them to participate, were you ever afraid even to contact them?

As I was writing the script, I came to the figure of the German soldier Hans. Immediately, I felt the ideal person for this role would be Stellan. For a while, the notion whirled around inside my head, but then I realised that because the novel was so internationally acclaimed, I really could, without any embarrassment, make inquiries with any actor. And that’s what I did. For some of them, I worked through an intermediary, the agent Tatjana Detlofson, but I contacted Stellan myself. In fact, we had met twenty-six years earlier in Prague, entirely by chance. Since then we hadn’t seen each other and in the meantime, he’d become an international star. I got through to him on the phone, and when I introduced myself, he immediately said, “My God, Václav!” – and then he agreed that I could send him the screenplay, he’d read it and then we’d see. So Stellan was the first who confirmed an interest in acting in the film, and that interest was very important during the negotiations with all the others. Of course, the essential point for all of them was that, first of all, they must like the screenplay.

I hear that you developed a particular ritual to celebrate the final take of each key actor’s work on the film?

It happened completely by chance, after we finished filming the chapter titled “The Miller”. After the final take, I and the entire crew said goodbye to Udo Kier. Something came to me suddenly, and I grabbed him around the waist, lifted him into the air, and shook him like a sack of potatoes. And then this became our ritual. For every male actor, after the final shot I always picked him up and shook him!

What was the most difficult challenge in these nearly eleven years?

Understandably, it was the financing, which lasted four years. I contacted dozens and dozens of producers across all of Europe without success. Honestly, there were times when I thought I’d give up, or at least in weaker moments, I flirted with the idea. But deep inside, I knew that I wouldn’t do that. I could not do that. The Painted Bird was my love, that I had to work on it, that everything that I felt and feel about this book had to be on the screen.