27 April 2022

Digitally restored classics Daisies & The Joke back on the big screen

Digitally restored classics Daisies & The Joke back on the big screen

Films created during the Czechoslovak New Wave attracted the attention of censors. Particular scrutiny was directed towards Daisies, a mischievous morality play from Věra Chytilová. After August 1968, the list also included The Joke, filmed by Jaromil Jireš based on the novel by Milan Kundera. Now, thanks to the Národní filmový archiv, Prague, both films are returning to cinemas in digitally restored versions. Daisies will be introdced in Cannes Classics and The Joke will have its renewed premiere at Karlovy Vary IFF.

Article by Martin Šrajer for CZECH FILM magazine / Summer 2022

In 1963, a character study aptly named Something Different premiered in Czechoslovak cinemas. After years of schematic dramas and comedies about the building of socialism, this realistic double portrait of a housewife and a gifted gymnast offered a truly refreshing change. The film was the feature debut of Věra Chytilová, a key figure in the Czechoslovak New Wave and the first female director to graduate from the FAMU film school in Prague.

While her classmates and older directors shot mostly misogynistic stories about stray men, Chytilová took female subjectivity into account from the beginning. In the making of her early films Ceiling (1961), A Bagful of Fleas (1962), and Something Different, she drew on the techniques of cinema verité to capture the everyday life of her protagonists as authentically as possible. Following that, she took a step in an unexpected direction, joining forces with the multitalented artist Ester Krumbachová and the topflight cinematographer Jaroslav Kučera to make the strikingly stylized Daisies (1966), which continues to entertain and provoke even now, more than fifty years after its creation.

Although Czechoslovakia experienced a cultural and political relaxation in the 1960s, Chytilová’s new film was considered formally too radical, even for its time. Whereas Something Different was seen as a distinguished project in the eyes of the country’s cinema authorities, Daisies was viewed as a dubious experiment, something best avoided by domestic filmmakers. The ideologues of the Communist Party’s Central Committee feared that the metaphorical language and absurdity of the main characters’ actions would confuse viewers to the point that they wouldn’t know what to take away from the film. Yet that was exactly the author’s intention.

The story of two girls, introduced as Marie I and Marie II, who decide to be just as rotten as the world around them and start filling their days with idleness, seducing older men, destroying things and consuming food, is broadly open to interpretation. We can understand it as an attack on the establishment, as a joyous celebration of women’s sexual liberation, or as a skeptical critique of nihilism and the decline of social morality and relationships.

At first the film was based on “Chudobky” (Daisies), a short story written for Chytilová by screenwriter Pavel Juráček. It told the tale of a pair of girls who killed time by engaging in pranks at men’s expense. Only fragments of this made it into the subsequent screenplay as Chytilová and Krumbachová made a children’s game called “Vadí nevadí” (Truth or Dare) into the guiding narrative principle. What had initially been a realistic glimpse into the lives of two young women became instead a “philosophical document in the form of a farce,” with traditional plot replaced by variation and repetition, modeled on musical composition. The men heading Barrandov Film Studio, where the film was to be shot, began to grow wary.

The state’s main censorship body gave the screenplay a negative assessment, mentioning the girls’ “gross cynicism” and their offensive lifestyle, which the author took no position on. Chytilová was advised to give the heroines an identity, psychology, and past that would explain their ostentatious flaunting of social conventions. She was also asked to remove the vulgarities from the script, as well as hints of a lesbian relationship between the girls.

The director partially gave in to the censors, and eventually the script was approved, despite their reservations. But other complications arose in the course of postproduction, when it became clear that the film contained many improvised dialogues and the composition of the shots didn’t correspond to the approved version of the script. The service copy was rejected by the authorities in February 1966. Although the creators anticipated that Daisies would be experimental, unrealistic, and disrespectful, the outcome of their subversiveness exceeded their expectations.

It wasn’t until July 1966, and after considerable editing, that the film was given the green light. Money also apparently played a role. Daisies, shot on imported color film, was by that point already being sold abroad. If it had been banned, the state would have lost the money it had invested, along with the opportunity to earn hard currency. Even after that, distribution in Czechoslovakia didn’t go smoothly. Officials continued to debate whether or not Daisies should even be released in cinemas, and the press weren’t allowed to write about the film, so the public never knew why a film that had been finished for several months didn’t premiere until December 1966.

Chytilová intended her satiric parable as a polemic against modern society and authoritarian male language. Fragmented editing, perspective-distorting lenses, accelerated and slow-motion shots, color filters, extravagant decorations and costumes, Art Nouveau crossed with fashion-magazine aesthetics — all of this was combined, but not in such a way as to achieve harmony. The combination of high and low, or ugly and beautiful, reflected the position of women who were prevented by society from creating meaning, and therefore resorted to ruinous anarchy and games. With their irrational, unmotivated actions, Marie I and Marie II reveal the hidden charm of destruction.

By rejecting patriarchal norms, Chytilová sought to tear viewers from their lethargy. And indeed the public, especially when it came to men, was not at all indifferent. The sharpest criticism came from an MP named Jaroslav Pružinec in May 1967, during a hearing on New Wave works in the National Assembly. He demanded a ban on distribution of several films, especially Daisies and Jan Němec’s A Report on the Party and the Guests (1966). Though he didn’t win his argument, nevertheless it confirmed Chytilová’s ability to capture the absurdity of thinking at that time, as apparently what bothered Pružinec the most was the apathy of the two Maries: he was outraged by the waste of food during the feast in the final scene.

In the spring of 1967, at the same time as Pružinec was trying to ban Daisies, Milan Kundera’s first novel, The Joke, was published, broaching the taboo topic of political oppression in the East bloc during the 1950s. This polyphonic contemplation of individuals’ powerlessness in the context of history enjoyed great success among Czechoslovak readers, who quickly bought out the print run, as well as in the West. A year later, in the liberalizing atmosphere of the Prague Spring, Kundera’s novel received the Union of Czechoslovak Writers prize and it was turned into a movie. The acclaimed writer had reservations about the previous adaptation of his work, the tragicomic Nobody Will Laugh (1965). So for The Joke, Kundera collaborated from the very beginning with director Jaromil Jireš, who for several years had sought in vain for a suitable project following the debut of his emotional drama The Cry (1963). The two of them wrote the screenplay together even as the novel’s manuscript was being censored.

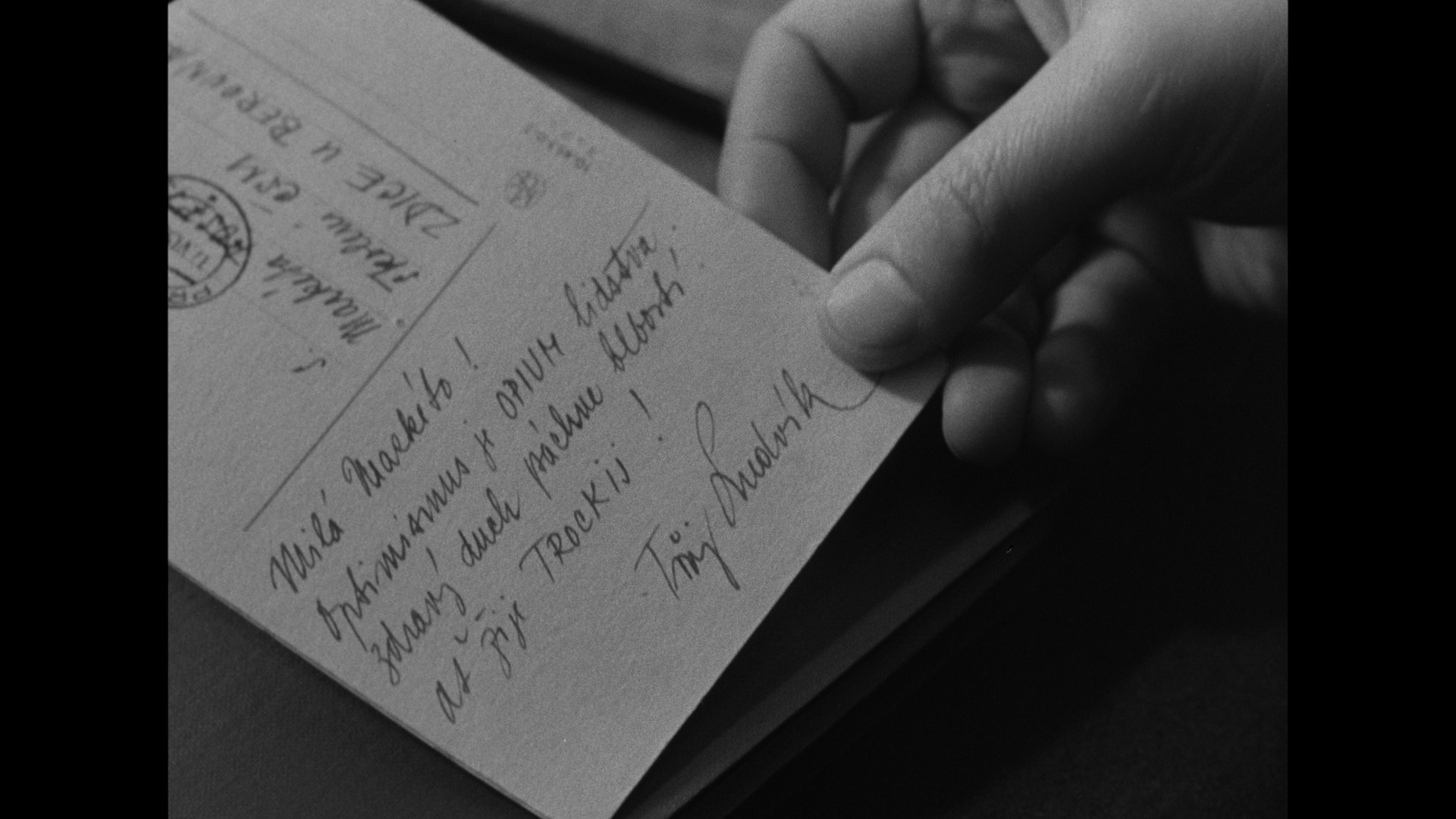

While the novel alternates between four narrators, the film has just one central character, Ludvík Jahn, who sends a postcard to his girlfriend and colleague, saying, “Optimism is the opium of humanity! A healthy spirit stinks of stupidity. Long live Trotsky!” When Jahn’s girlfriend turns the postcard over to officials, he is expelled from the Party, fired from his job at the university, and sent to a labor camp. Many years later, when the main part of the drama plays out, he remains a man who, due to the past, is unable to experience the present.

In Jireš’s film, past events are constantly creeping into the present. Jahn encounters people and situations from the distant past on the street, in his dreams, and while looking in the mirror. He is still stigmatized by the past. When coincidence presents him with the wife of a former classmate who helped ruin his career, he decides to seduce the woman. However, revenge has a painfully ironic outcome. Kundera was pleased with the compositionally and rhythmically balanced film, which emphasizes the tragic aspects of the book, rather than its irony, and convincingly evokes feelings of depression and defeat. According to the author, Jireš chose excellent actors, created a convincing atmosphere, and alternated masterfully between emotions.

Nonetheless, in April 1968, Kundera was identified in a dispatch of the Soviet Union’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a member of a group seeking to overthrow socialism in Czechoslovakia. After the August invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops, he was at the top of the list of undesirables. The Joke was withdrawn from bookstores and libraries at the beginning of 1970. Kundera first left FAMU, where he had been lecturing, and then left Czechoslovakia altogether. Although Jireš’s film was not subjected to criticism as harsh as Daisies, and its further release was even briefly considered, it too was ultimately pulled from distribution. The attempt to critically come to terms with the socialist past or present, an aim that is at the heart of most Czechoslovak New Wave works, was no longer desirable. The golden ’60s were over.