05 February 2017

The Mastery of Jan Nemec, Rediscovered

The Mastery of Jan Nemec, Rediscovered

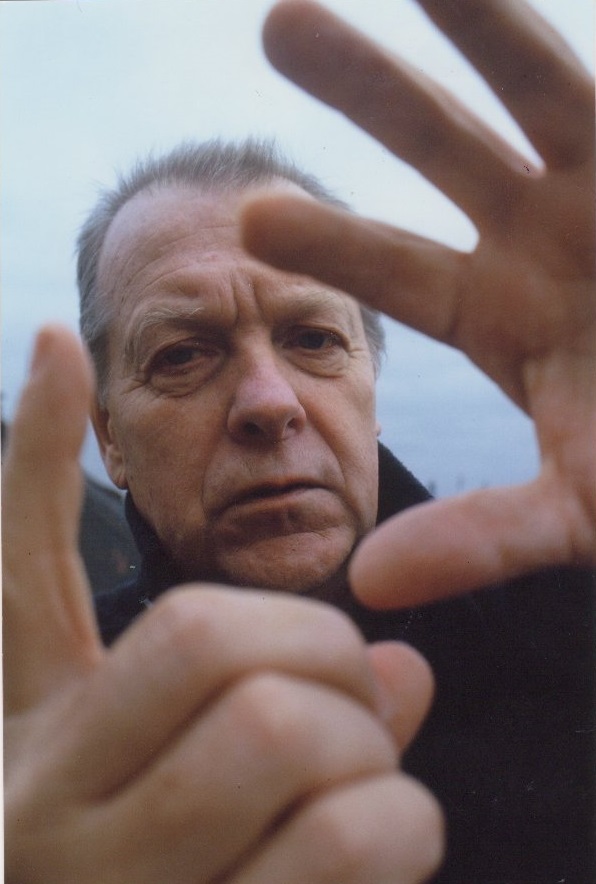

Director Jan Němec passed away in March 2016, just days before the last scenes of his final feature, The Wolf from Royal Vineyard Street, were shot. Now, in advance of the film’s international premiere, at the 46th International Film Festival Rotterdam, which will also feature an extensive retrospective of the intrepid director’s more than 50-year career, we offer a selection of reviews of his work from the pens of international film critics, who paint him as a compelling auteur for our times.

Article by Irena Kovařová for Czech Film Magazine / Spring 2017

The IFFR 2017 program celebrates one of the most clear-eyed artists the Czechs have ever had, an uncompromising voice not only in film, but also in the public realm. Němec made more films after the fall of communism in 1989, than during the “film miracle” of the 1960s Czechoslovak New Wave, and this year’s Rotterdam festival presents an in-depth exploration of his oeuvre, covering the breadth of his life-long career. It will be the largest retrospective of Němec’s work ever programmed by an international festival, in- cluding several of his films screened with subtitles for the first time. In addition, all the staples of the auteur’s filmography — Diamonds of the Night, The Party and the Guests, Late Night Talks with Mother, and Toyen — will be screened, in pristine archival 35mm prints.

In “Off the Blacklist: The Films of Jan Němec,” pub-lished during the 2013–14 touring retrospective of Němec’s work in North America, Max Nelson, writing in Film Comment, offers a close look at Němec’s first three features, describing them as the source text for the Czechoslovak New Wave: “The films have, among other things, the same brand of slapdash anarchism as Věra Chytilová’s Daisies; the same clipped, elliptical approach to storytelling as František Vláčil’s The White Dove; and — at least in the case of Martyrs of Love — the same sensitivity to the pangs and pitfalls of first-blush romance as Jiří Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains. But where his New Wave colleagues (Vláčil and Chytilová in particular) tended to aspire to a kind of filmed poetry, in which each image feels as if it’s always wrestling out of its narrative context, Němec seems most at home making the cinematic equivalent of novellas.”

Nelson continues: “In Němec’s cinema, abstract questions — What makes us free? What, if anything, serves as a stable basis for political authority? What makes us un-free: ourselves or others? —a re borne concretely out in the movement of bodies: at some moments penned chafingly in, at others set in nervous, unstable motion.” Nelson notes that Němec demonstrates this trait from his very first feature, Diamonds of the Night, praising the director for his economy of style. Nelson writes that Němec wastes no time on exposition, to “startling effect.” He goes on: “It’s immediately evident that [the boys are] running for their lives — which, it soon becomes clear, means that they’re running primarily for the freedom to keep running.” He also comments approvingly on the “breathless, associative editing” and the director’s decision to forgo historical context in favor of “distilled emotional truth.”

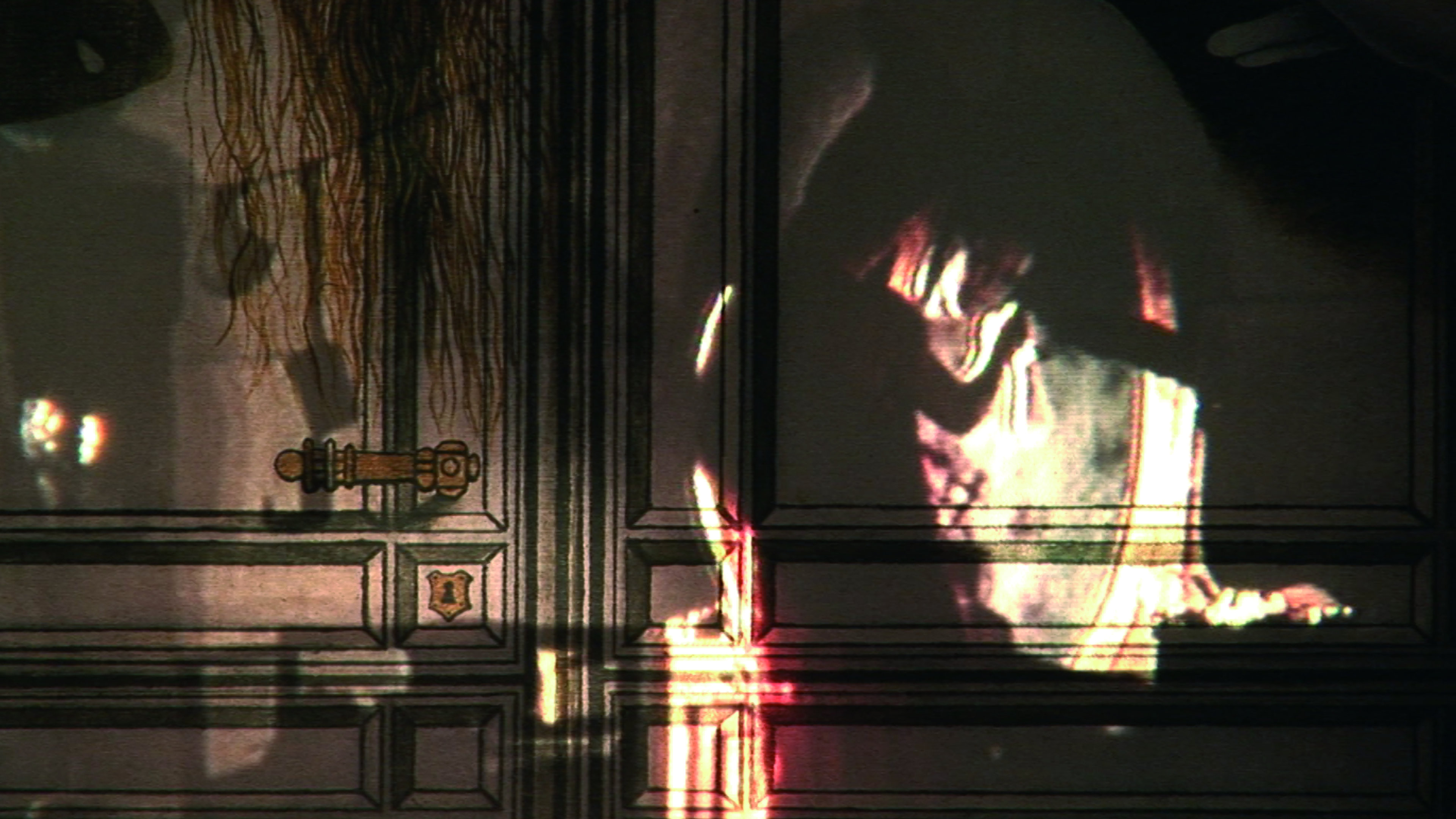

Diamonds of the Night

“A brilliantly stylized and tensely disturbing study”

Dave Kehr, New York Times

Němec’s second feature, The Party and the Guests, “is widely considered [his] most politically charged,” writes Nelson. The director “has a sharp ear for the kind of psychological manipulation practiced by regimes in his day [. . .] yet it would be a mistake to read the film as a direct, one-to-one allegory.” In fact Nelson considers the film to be closer to parable: “Ultimately, it has less to do with this or that authoritarian regime than it does with the fragile nature of human freedom, and the capacity of people to let themselves be corralled within a certain prescribed system of thought.”

“Němec has often cited Kafka as a formative influence, and Party can be seen as one of his most direct attempts to find a cinematic analogue for his literary hero’s deadpan, slightly stiff, disarmingly blunt prose style. With its unexplained-imprisonment scenario, the film echoes The Trial, but it’s arguably closer in spirit to one of Kafka’s Zürau Aphorisms: ‘a cage went in search of a bird.“

Finally, Nelson writes of the third feature film, “whereas the conflicts in Němec’s first two films boiled down, at least on one level, to bodies having their freedom of movement physically constrained by outside forces, Martyrs of Love takes place in something closer to a prolonged dream state, where external conflicts tend to act as surrogates for inner ones.”

Critic Eric Hynes, in his Time Out New York 4-star review of Diamonds of the Night, writes: “Jan Němec’s debut stunner feels even more potent now that it’s been freed of the expectations and delineations of a national movement. In 64 fleet minutes, we’re utterly and overwhelmingly immersed in a Jewish fugitive’s singular experience, from hunger pains to hallucinatory reveries. Němec’s technique is as emotionally intuitive as it is masterful, purposefully scrambling past and present, handheld realism (a breathless opening tracking shot) and Buñuelian surrealism (fever-dreamed ants colonizing [the boy’s] angelic face). It’s a torrent of life — and cinema — in the face of death.”

In another glowing review of Diamonds, Glenn Kenny writes for MUBI.com: “What we are in store for is not merely — as if ‘merely’ is the right word for such a thing — a historically grounded artistic simulation of the massive psychosis we refer to as ‘war,’ but a magnificent and piercing existential riddle.” Kenny concludes: “This is one of the most intensely concentrated films of all time.”

Graham Fuller, in his article for Blouin Artinfo, pays special attention to Němec’s surrealist influences: “Sig- nificant among his later works are his self-portrait, Late Night Talks with Mother, and Toyen, about the eponymous Czech Surrealist painter and illustrator of feminist erotica who had sheltered her Jewish artistic partner Jindřich Heisler during the German occupation.”

Fuller continues: “A believer in ‘pure film,’ Němec was always drawn to the unconscious language and imagery of Surrealism. Although he is wary of giving too much credit to his influences, there are trace marks of Luis Buñuel and avant-garde era René Clair in his movies, especially Martyrs of Love (1967), a delicious non-political musical comedy.“

The Party and the Guests

“A daring satire on power relations under the Communist government”

Dave Kehr, New York Times

“Constructed with effortless economy, sharp-edged and riveting”

David Wilson, Monthly Film Bulletin

Martyrs also pays homage to the elegant farcicality of classic American silent comedy and, in its use of jump cuts and shots of characters looking directly into the camera, to the nouvelle vague. Except for the sound effects and chansons and jazz tunes Němec includes, the film is itself virtually silent, containing just a few spoken lines — as if, in matters of love, words are redundant. [. . .] More potent than the storytelling is the sensuousness and humanity conveyed through Němec’s poetic eye and his delight in the medi- um’s plasticity and the musicality of editing.”

Peter Hames, in his book The Czechoslovak New Wave, the definitive assessment of that era, writes: “Němec’s films have not achieved the same international reput tion as the work of Forman, Menzel and Chytilová. One reason probably lies in their brevity, resolute experimentation and occasional rough edges. Němec admitted that all his films were made in a rush for fear that he would not be allowed to complete them, [yet] the speed with which the films were made gives them an urgent individuality that is one of their most attractive features.“

“There is also a cultural barrier to the appreciation of Němec’s work. Despite the pretensions to universality, The Party and the Guests undoubtedly means a great deal more when seen as a comment on the Czechoslovak experience, while the particular Poetist/Surrealist tradition that gave rise to Martyrs of Love can be regarded as an acquired taste. They are, nevertheless, films that reward repeated viewings, and have been unjustly neglected by foreign audiences.”

Hames concludes: “[. . .] dedicated to the concept of a personal style of filmmaking, Němec made no concessions in his attempt to develop a nonrealist cinema.”

Michael Koresky writes, in his essay accompanying The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse edition of The Party and the Guests: “At once whimsical and frightening, it confronts its audience with unsettling social realities. And though its message — simplified, that people are all too willing to be manipulated and controlled — resonated with viewers everywhere [. . .], in Czechoslovakia it was downright incendiary.”

In her aptly titled “Czech Master Rediscovered,” Kristin M. Jones, writing for the Wall Street Journal, describes “the startling early feature Diamonds of the Night” as “a feverish blend of beauty and terror.” She suggests that “the work of the director . . . deserves to be seen more widely,” and of his late works concludes, “Probing eloquently into the layers of the past, Mr. Němec’s nonfiction films are further evidence of a remarkable life and career.”

Ivana Košuličová comments, in Central Europe Review, that Němec, building on the Brechtian model of epic theater, “does not want the viewer to experience emotions based on the identification with film characters. He tries to provoke a philosophical, spiritual reflection about the themes that are presented in a film.” By employing supreme stylization, Košulicová writes, “he creates a new specific spiritual world that reflects his thoughts and fears and testifies not only about himself, but also gives a general testimony about human existence.” This, she argues, is evident throughout the director’s oeuvre.

A. S. Hamrah writes, in his notes to the touring program for Harvard Film Archive: “Němec’s films have a toughness of their own. More clear-eyed, less wistful, and weirder than the films of his compatriots, their sense of freedom amid repression and hope within darkness now appears to have sealed Němec’s fate as much as any overt political provocation did. Poised between the anarchic confrontations of Věra Chytilová and the humanist whimsies of Miloš Forman, Němec’s films are terse and absurd, snatched from real life in a country that no longer exists but whose problems Němec presented as universal. Recent events in Ukraine show they are timely today.”

“The idea of making a retrospective came up two years ago, after The Wolf from Royal Vineyard Street was presented in Karlovy Vary as a work in progress. Ever since then, we’ve been waiting for Němec to finish his new film, though of course we never thought things would go the way they did. He passed away soon after completing the film, which was tremendously sad news for everyone. Still, we don’t see the program as a postmortem tribute, or anything remotely like that. In fact, the incredible playfulness of Němec’s work suggests that he himself would be opposed to any formal-type memorial. It’s also the most extensive retrospective of his work ever assembled. Many of these films are being shown internationally for the first time, which we hope will trigger more interest in his diverse and very special oeuvre.”

Evgeny Gusyatinskiy, IFFR programmer and co-curator of Jan Němec retrospective (with Irena Kovarova)