02 October 2022

When I break everything down, that’s when the chemistry starts to emerge

When I break everything down, that’s when the chemistry starts to emerge

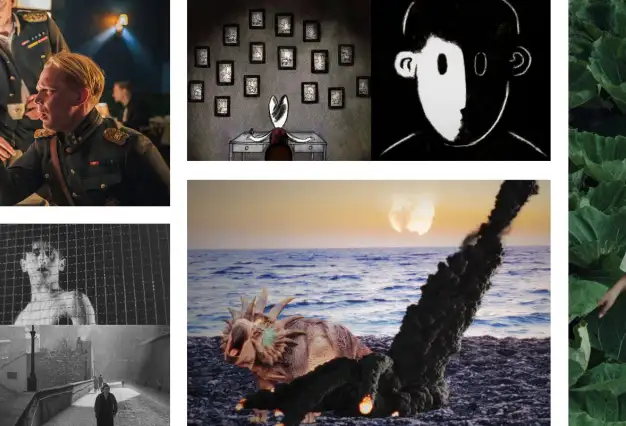

Šimon Hájek claims inspiration not only from art films like Markéta Lazarová but also the action-packed Under Siege. He openly airs unorthodox views on FAMU and Czech cinema. He makes no bones about buying his artistic freedom with work on commercial projects. And so far, he’s had a string of films screened in the Great Hall of the Karlovy Vary IFF: Domestique, King Skate, At Full Throttle, and, this year, BANGER. Born in 1984, Hájek is currently one of the most interesting—and hardworking—editors in Czech film.

Written by Vojtěch Rynda for CZECH FILM / Fall 2022

You edit feature films and documentaries, TV series, music videos. Is there any one thing that you enjoy most?

I enjoy everything. Sometimes I just have too much. I just like making the audience happy, that’s what fulfills me. Plus I also edit “endless” series like Ulice. It’s better to be able to make money on commercial projects, then have the freedom to do what I want the rest of the time, instead of whining to the director in the editing room that I don’t have money for bread. I’ve worked on reality shows like Survivor and Vyvolení. My colleagues used to say, “How can you do that?” It made me sad. Then the film critics’ magazine Cinepur called Vyvolení the best TV show of the year!

You started getting more recognition after Šimon Šafránek’s documentary King Skate, about the 1980s skateboarding scene in Czechoslovakia, which won a number of awards, including the Czech Lion. How did you come up with the structure, based on the clash between freedom and oppression under communism?

We had a lot of archives from guys who skated in the ’80s. The footage was really interesting, but it wouldn’t have been enough on its own, we needed another layer. We had some TV archives ready to go, but the material was purely informational. Then I saw a report on TV about how a large percentage of Czech university students today have no idea what the Soviet invasion of August 1968 was. So the next day I told Simon, “Listen, young people are going to watch this film. Let’s show them how evil the communist regime was.” And the freedom from those archives began to collide with the totalitarianism in the images of the television of that time. That’s what made the film.

You work with the archival footage in great detail.

That’s what director Jitka Rudolfová taught me. When I was editing something with her and I would dump, like, twelve archive shots in at a time, she would say, “Don’t be lazy, cut it up!” Now I know that when I cut everything up and break it down and it starts to collide with everything, that’s when the film’s “chemistry” starts to emerge. It’s the same with sound. As Godard said, synchronous image and sound represent the “end of cinema”.

This year you returned to the official selection of Karlovy Vary with BANGER., which is set in Prague’s hip-hop and drug scene. Was that different for you?

Definitely. For time reasons, there were two of us cutting that film. Jakub Jelínek had to go through all the material and put together the scenes, which I then reworked with a clean look and gave them a certain style. Then it was Jakub’s turn and finally my turn to make sure everything fit. Adam Sedlák, the director, poor guy, had to sit through it all. Basically, he edited the film twice.

How did you get into editing?

I went to a film festival, basically by accident, and saw von Trier’s The Idiots and Vinterberg’s The Celebration. I had no idea what I was seeing. From then on, I started going to the cinema club to see two films a day for two years straight. I was only accepted into FAMU on my third try. I thought that as an editor I would “ride along” with a director and learn everything from them. Nobody ever told me that as an editor I’d have to go through six hundred hours of material.

How did FAMU influence you?

Not a lot. I grew up watching TV and action movies like Total Recall and Under Siege, and I edit accordingly. It’s an American style that I mix with a European art style, like Lars von Trier, Joachim Trier, or Haneke.

Under Siege with Steven Seagal?

Yeah, movies where someone hijacks a train or a ship or whatever probably won’t change the world for the better, but you can learn a lot from them. Who’s the protagonist in Under Siege? The ship! The ship drives the plot, Seagal’s character is just a tool. And when the helicopter lands with the antihero in the exposition, it’s like Hitler's arrival in Triumph of the Will…

How do you recognize a good editor?

By when they stop editing. They’re not messing around with scene continuity and they’re paying attention to how the film plays as a whole. They’re not concerned with editing anymore but making a movie.

Do you have any favorite editors?

Maybe Dylan Tichenor. Miroslav Hájek is phenomenal, especially in Markéta Lazarová. Then I like editor-fixers like Stuart Baird, who gets called in when something needs fixing. Like Street Fighter—I edited the ending of At Full Throttle based on that film.

At Full Throttle is a documentary about a man from a Moravian village who does autocross racing and struggles to find his place in society. It was also in the main competition at Karlovy Vary last year. What made it interesting for you?

It was purely observational. But when I lined up the material with director Miro Remo, who had as much input as I did on the editing, we saw an interesting man who was great at what he does, but no real subject matter. So we decided to explain the frustration of people who are getting disillusioned with society and leaning towards the far right. We tried to make it so viewers from a certain social class who tend to despise people like that would say, “I would normally hate this person, but suddenly I understand him.” I feel like that’s extremely important. Those kinds of things are the reason I edit films.

Is it the theme-finding phase that you enjoy most about editing?

Well, that’s what editing is all about. It’s not hard to put shots in order, to “carry the coal,” so to speak. There’s nothing hard about that, it’s just exhausting sometimes. Actually that’s the problem with most Czech films: they’re edited so that the scenes follow each other, shortened to a given length, and given a beginning, middle, and end. But I think that’s the stage when the real editing begins: when a film is “playing,” that’s when you have to start figuring out what it’s actually about.

You and Remo are now working on Better to Go Mad in the Wild, about three generations of modern-day hermits, including the twins František and Ondra Klišík. What did you take your cues from while editing this film?

The Klišík brothers have lived together their whole lives. Neither one of them has a wife or children, and they both do quite a lot of drinking. It’s hard to come up with a story there. So we found the most powerful moment, when their beloved animal dies, and tried to build around that point.

You’re working with Petr Hátle now—for whom you edited, for example, the documentary The Great Night (2014)—on his feature debut, Mr. and Mrs. Stodola, based on the true story of a serial-killing couple. What do you find specific about that film?

The material is beautifully shot, and dark, and Petr knows exactly what he wants. Lucie Žáčková and Jan Žáček are phenomenal in the roles, and it has a tension I haven’t seen in a long time.

You have a reputation as one of the hardest-working Czech editors in the industry.

I’m also working on a documentary about foreclosures with Ivana Milošević and Barbora Chalupová. The idea is to show people in debt that they can get out of debt, that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. The idea of not having a job scares me. For example, I’ve learned to edit in four different programs on both PC and Mac, so I can work with anyone. And when I promise to work with someone, I refuse to go back on it. I do a lot, but as the line in The Man from Acapulco goes, “I’ve written 42 books. Bad ones. But I think there’s about five decent pages in each of them.”