16 January 2020

Get inside the mind of Karel Vachek

Get inside the mind of Karel Vachek

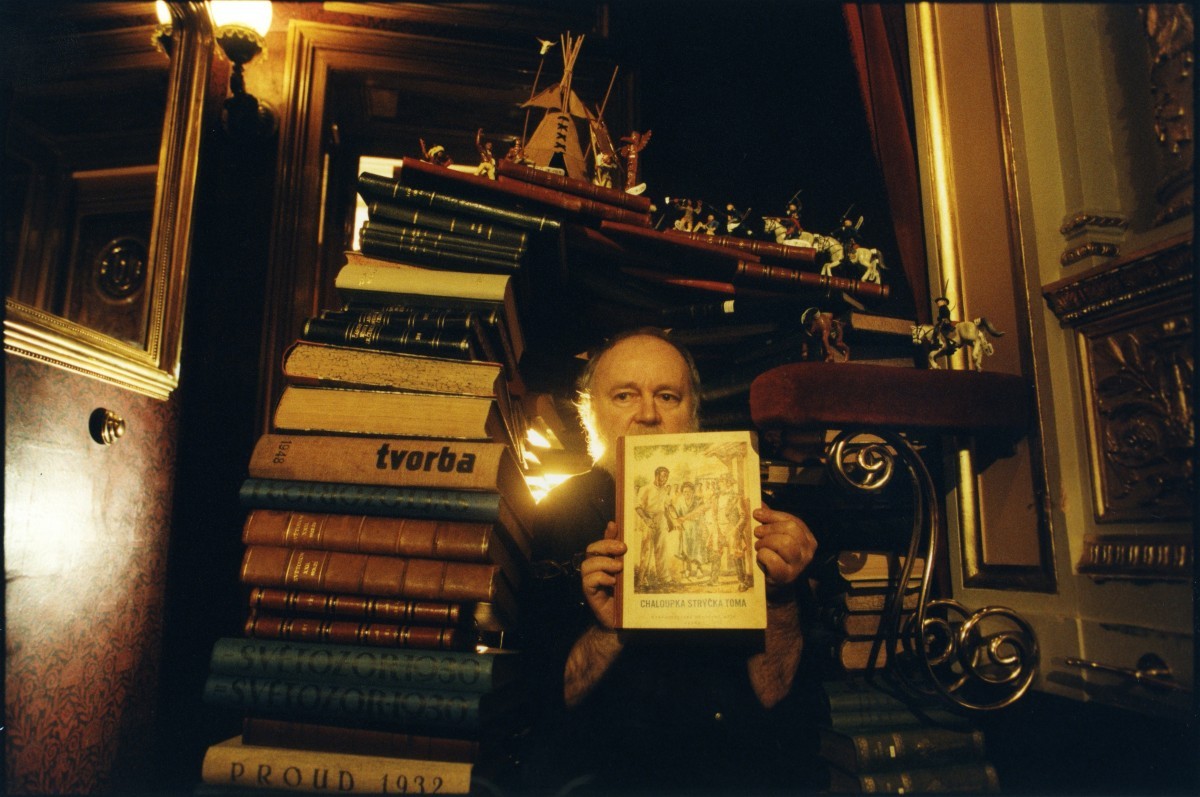

This year, legendary Czech director Karel Vachek will be internationally premiering his latest opus, Communism and the Net or the End of Representative Democracy, in The Tyger Burns, a program of the Rotterdam International Film Festival that highlights “the gaze of the old filmmaker.”

Article by Petr Fischer for Czech Film magazine / Spring 2020

The Tyger Burns (a reference to the William Blake poem “The Tyger,” with its famous line “Tyger Tyger burning bright”) features new and recent films by directors who were already active when the Rotterdam festival started in 1972.

The films of Karel Vachek do not fit very well into the traditional genre categories that we usually use to think about cinema and other art forms. The imagery of his films spills over and out into an in-between space where we struggle to put a name to what we are seeing. Although not a problem for the films themselves, which, thanks to their editing structure, infiltrate the viewer’s mind quite naturally, their indeterminate form defies categorization, and therefore — not paradoxically but unavoidably — a more personal understanding.

It is probably human nature that most of us need a map, or at least some basic bearings, before we are able to step into a labyrinth of images and characters, and allow its magic to speak to us.

In Vachek’s films, this problem is addressed through two words: essay and novel. This is meant to suggest that a film is always nothing more than an inconclusive attempt to draw attention to the way the mind is in motion, to capture the movement of thought, a goal best achieved through a long, extensive narrative that, as Walter Benjamin wrote, attests to the failure of human dreams to grasp the mystery or essence of life.

Vachek’s latest project, a four-part, nearly six-hour opus titled Communism and the Net or the End of Representative Democracy, is notable for not only not accepting Benjamin’s thesis concerning the essence of the novel, but deliberately refuting it, as it strives to arrive at the mystical source that gives rise not merely to art, but to the art of living if not life itself.

Inspired primarily by the work of his brother, Petr, a painter of enormous canvases, Vachek attempts to create an all-encompassing film, taking in everything, a “grand tableau” of colossal proportions, a Bosch-like bulletin board of the world.

“There can’t be just something there, there has to be everything,” says Petr in the film — though speaking of his painting, he could just as well be commenting on the approach of Vachek’s film itself.

As a matter of fact, we see this same expansiveness in the other works Vachek has made since 1989: in particular in the tetralogy The Little Capitalist — New Hyperion or Liberty, Equality, Brotherhood (1990–92); What Is to Be Done? (A Journey from Prague to Český Krumlov or How I Formed a New Government) (1993–96); Bohemia Docta or The Labyrinth of the World and the Lust-house of the Heart (A Divine Comedy) (1997–2000); and Who Will Watch the Watchman? Dalibor or The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2001–02) — as well as the same attempt to include, insofar as possible, everything important. Vachek’s aim has always been to show the transformation of society and consciousness in what is not immediately visible yet nonetheless, unobtrusively, arranges the life of the whole.

In some sense, this is the opposite of what Vachek did when he started out making films in the ’60s. Whether in his famous work Moravian Hellas (1963), which dealt with the growing irrelevance of folklore, or the lesser-known Elective Affinities (1968), examining the election of a president, Vachek was enamored with the immediacy of contact sound while having a camera on site to capture the action, and his preferred format was (pseudo)reportage.

Here the filmmaker is exploring particular phenomena: the rawness of folk culture and its cultural abuse; the presidential election as a political process — these form the frame of the film, the borders within which his compositions of imagery are played out.

Post-1989, he no longer made “reportage,” abandoning phenomena in favor of background and assumptions. Vachek turned his attention to the manifestation of things, the process by which something emerges and becomes apparent, becomes an image, though what matters to him is not the image as such, its content and form, but what it emerges from and how its appearance occurs. In this regard, Vachek’s filmmaking resembles the movement of modern phenomenology, which in the wake of Husserl and the exhaustion of his scientific concept of philosophy, can only be maintained by turning from pure phenomena to pure manifestation or revelation.

The stream of images Vachek produced after 1989, then, resulted in work completely different from his previous films in terms of structure and internal logic: curious mosaics in shifting configurations, like mental maps composed from the thoughts of “the people in the center” and “the people on the margins,” maps on which, in hindsight, we can recognize the historical movements we lived through but were unable to perceive clearly while they were taking place, to say nothing of the substratum from which they sprang.

Yet it is precisely this essential “invisibility” that is carefully preserved and intensified in Vachek’s imagery. This is also why his films are best understood and speak most powerfully with the passing of time; over time they grow, increasing in intensity and flavor: they ripen.

At first glance, Communism and the Net, or The End of Representative Democracy exhibits the same novelistic approach seen in his earlier works. Again, a curious mental structure grows before our eyes, and though we may be looking in at it from outside, it is simply a mirror image of our day-to-day reality — albeit with one important difference: While in previous films, some more or less open space remained, both inside and outside of the structure, since the goal was to depict a slice within the space-time continuum, this time Vachek seeks to achieve a closed space of absolute perfection, in an attempt to create an all-encompassing film with the same magical effect as the paintings of his brother Petr (or like those of Hieronymus Bosch, in which what appears to be a chaotic configuration is actually perfectly and precisely organized, as revealed by compositional drawings underneath the paint in Bosch’s large tableaux, recently discovered thanks to X-rays).

There are two ways in which Vachek as director attempts to create the perfect “omni-film”. The first is by the enormous compilation editing of his own work; the second by overloading his images with additional meanings, exposed and superimposed on top of one another as if we were watching the appearance of a secret message in invisible ink, the revelation of some cultural palimpsest.

So fascinated is the director with the modern concept of “the net” that he sees it everywhere — in maps of artists and authors, in a stream of images of great books and important politicians, in compilations of quotes, imposing an older, literary order on the endless stream of images.

All these webs of associations are woven into the foundation of the world as we experience it; they are not random but in fact constitute the mystical structure of the universe, which normally remains unseen although we can certainly sense it (here we see the senses taking precedence over reason; the influence of Vachek’s sister Ludmila), and we can also make it visible through art — writing, painting, and film.

Having expanded on the subject in his book A Theory of Matter: On Inner Laughter, the Schism of the Mind, and the Centrality of Fate, now Vachek attempts to depict on screen: through imagery and the recomposing of images, but most of all through editing, which, as demonstrated by Orson Welles, among others, is where the true magic of cinematography lies.

As Vachek himself says: “Note the way it is edited. You see, that is where the inner laughter is hidden. I’ve seen it already at least fifty times, and I still laugh.”

And what we should be paying the most attention to? “There are two ropes we cling to in life. One is our encounter with what is given, causes and effects; the other is our encounter with the essence, also known as God,” Vachek explains in his film as he also does in his book. God, he says, is merely a different type of given, taking his inspiration from the philosophy of Spinoza. In his view, we are so afraid of this separateness that we live an illusion of free will to keep from going mad because of the burden we would bear otherwise. “And yet, the only freedom we really have is to remain in God.”

Provided we can ignore the undeniably self-referential framework of Communism, which may get in the way for many, since really what we are watching is an exploration of Vachek’s mind and his attempt to remain in God, the film shows us a whole new world. It is not just a panopticon of society, where the politicians of today meet those of yesteryear, party leaders and popular singers come face to face — the Pope encounters economist Ilona Švihlíková or historian Jan Tesař while we succumb to the cleansing laughter that is, after all, the point of this work — but there is also a highly complex structure created, an interweaving of webs of reciprocal links and references, the reading and interpretation of which provides a useful guide on the road to freedom, when understood in the way Vachek has described. So it is also a net or a web in the sense that we commonly understand it today, that is, the digital interconnecting of free individuals, just another reflection, another configuration of God, which becomes the one who can save us.

Communism scoops up in its net everything important to society — politics, economics, philosophy, art — and finds a way through this tangled knot by means of editing. If you sit through all six hours, gradually you will see Czech culture revealed as the battlefield of a classic power struggle in which ideologies vie for dominance, with their power only now and then overshadowed by the charisma of a historical personality — the allure of a figure whose vision extends further or deeper than the know-it-all politician chasing money and power.

With his faith in “our Czechs,” who see through the world to the essence the 79-year-old Vachek so fervently seeks, there are times when the director can be incredibly irritating. His foursome of so-called national mystics — Ladislav Klíma, Edvard Beneš, Jaroslav Hašek, and Alexander Dubček — is also cause for great scepticism.

On the other hand, his obstinacy and doggedness in his lifelong quest for an essence that is often repugnant and callous toward humankind, as Communism demonstrates, ultimately wins our sympathy. In a world carried away by the trend for speed and high energy, Vachek continues to make slow, oceanic films that must be patiently and attentively read, like the good novels of the old days, filled with mysteries and revelations. At first, it may be boring and maybe even hard work, but anyone who makes it through the first half hour is guaranteed a rich reward in the end, the bliss of experiencing an everything-film.

That is a conviction shared also by the director, who, like his brother Petr the painter, would just as soon blanket his picture in Naples yellow to express the penetrative revelatory power of sunlight, a halo of eternity. There are at least flashes of this magical colour in the editing, which shines a new light on what Vachek has been doing all his life. So what about communism and the net and the end of representative democracy?

On the road to learning how to free ourselves of ideology (the ideology of power and of money) by following the essence, we are all equal; in the ideal egalitarian web of liberated individuals, there can be no talk of representation. When it comes to the freedom to remain in the essence, no one else can represent us. And somewhere around here is where communism begins...